By Camilla Ucheoma Enwereuzor

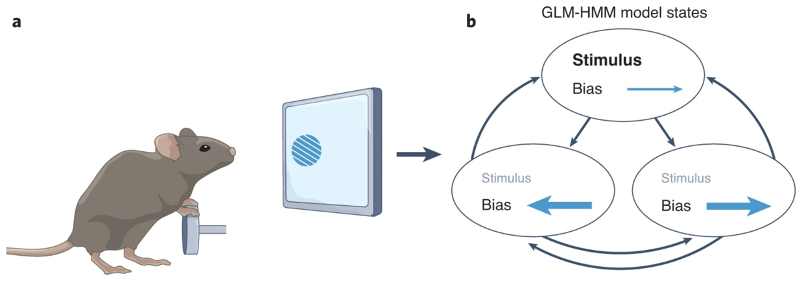

As part of my MSc internship in the lab, I have spent the last couple of months diving into a paper by Ashwood et al. (2022), who investigated how observers switch between different strategies for perceptual decision-making over the course of long testing sessions. According to previous accounts (e.g., Wichmann & Hill, 2001), subjects maintain one main strategy during cognitive tasks, and any lapses (i.e., errors despite strong sensory evidence) arise independently of one another and of the time course of the experimental session. However, Ashwood et al. suggest that this view is not correct. Using a modelling approach based on Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), the authors found that mice switch between multiple strategies, or hidden “states”, during perceptual decision-making sessions (Figure 1). Importantly, the Markovian component of this approach implies that states are not independent of one another, but rather depend only on the state from the preceding trial, and can persist for many trials in a row. Let us look at how this modelling approach works in more detail.

Figure 1. Reprinted from Figure 1a-b of Histed and O’Rawe (2022). a. Schematic representation of the task for the IBL et al. (2021) mouse data. Mice turned a wheel to indicate whether a sinusoidal grating appeared on the left or right side of the screen. b. Recovered states according to a 3-state GLM-HMM: mice switched between an engaged state where they relied heavily on sensory evidence, to less engaged states that showed left or right biases.

Ashwood and colleagues analysed perceptual decision-making data using a GLM-HMM. In a typical HMM, observations can be mapped to a set of discrete hidden Markovian states. Each state has different fixed probabilities of emitting a specific behaviour, like choosing left or right in a decision-making trial. Additionally, states can change according to fixed (self-) transition probabilities. The GLM-HMM used in the paper is simply an HMM where state/emission probabilities are not fixed, but instead governed by separate state-specific Bernoulli GLMs. Here, the weight vectors of the GLMs are what determine how inputs are integrated to emit a specific behaviour in each trial, and the shape of the corresponding psychometric function (Figure 2). Consider, for example, four different inputs (as in Ashwood et al.): stimulus properties, bias for one of the two options, the subject’s choice on the preceding trial (i.e., choice history), and whether the subject was rewarded on the previous trial. Different latent states are characterised by a specific combination of weights on these inputs, which manifest as distinct strategies during task performance. An optimally engaged state would see the highest weight on the stimulus, with little to no weight given to bias, choice history or reward history, resulting in highly accurate performance. Alternatively, a “win-stay, lose-switch” strategy would show less consideration for the stimulus’ properties and a larger weight for reward history, leading the mouse to repeat the choice that previously led to a reward. It is interesting to note that even in suboptimal states like the latter, the weight for the stimulus does not necessarily need to be zero. This is in contrast with the classical “lapse model” from earlier accounts, which assumed that lapse/disengaged states must be completely stimulus-independent.

Figure 2. a. Reprinted from Figure 2e of Ashwood et al. (2022). The figure shows the recovered GLM weights of a 3-state GLM-HMM for the IBL et al. (2021) mouse data. State 1 shows a large weight on the stimulus, indicating an engaged strategy with no influence of other biases. States 2 and 3 show a lower weight on the stimulus and larger weights for the bias input, reflecting leftward and rightward biases, respectively. b. Reprinted from Figure 2g of Ashwood et al. (2022). Psychometric curves corresponding to each of the three latent states.

Finally, the parameters obtained from fitting the GLM-HMM, i.e., the transition probabilities, initial state distribution, and the GLM weights for each state, are used to calculate the posterior probabilities of a subject’s state in every trial across the experimental session(s). This gives precious insight into the temporal evolution of strategy and task engagement over the course of long experiments.

In their paper, the authors analysed data from two mouse experiments (The International Brain Laboratory et al., 2021; Odoemene et al., 2018) and one human study (Urai et al., 2017) using different perceptual decision-making tasks. For all three datasets, multi-state GLM-HMMs performed significantly better than alternative models, like the classic lapse model or a simple one-state GLM. These findings show that GLM-HMMs are a promising tool for obtaining a better and more detailed account of latent processes in decision-making.

Understanding how strategies and engagement fluctuate during behavioural experiments opens up many interesting questions for research: should we only analyse data from trials where subjects are optimally engaged? What are the neural mechanisms underlying different states? What factors, be they related to arousal, behaviour, or clinical conditions, can predict state dynamics? And, since only one human dataset was included in Ashwood et al.’s paper: can these findings be replicated more broadly in human decision-making experiments? How might states and engagement fluctuations differ across species when performing the same task?

Originally, the goal of my internship was to replicate Ashwood et al.’s findings, and eventually work towards applying their modelling approach to a new set of human decision-making data. In my attempt to do so, I put together a flowchart of the analysis code used in the paper (flowchart available here). The original code is publicly available here, and while it is seemingly ready to use, I had to tweak some things to get it to run smoothly on my computer. You can find the updated code with my edits here.

Ashwood’s code is organised into different steps, split across many different scripts and folders. Although this organisation is quite neat, I have come to realise that you can only fully appreciate it if you already understand how the model fitting procedures work. Had you asked me three months ago when I first looked at the code, I probably would have described the organisation as confusing more than anything else! Indeed, it took me quite a long time to get the ins and outs of the model fitting, especially as it required many jumps between directories to follow the thread of how specific functions work and how data is handled. This rabbit-hole structure made it particularly difficult for a relative beginner like me to know where to look and how to fix issues when they came up.

This is where the flowchart comes in handy: it consists of a step-by-step breakdown of all parts of the analysis, with an emphasis on GLM-HMM fitting and cross-validation across different models. In addition, I noted down the names of the files and, where needed, the functions corresponding to every step: this should make it easier to look “under the hood” and pinpoint where things might be going wrong.

Detailed overviews like this one are also useful to more easily compare between different ways of using similar analyses. For example, Ashwood et al.’s GLM-HMM has recently been adapted in a preprint by Hulsey et al. (2023), who used it to analyse the relationship between arousal and fluctuation in engagement states during perceptual decision-making. While the two studies share similarities, there are interesting differences to note. Some are easy to spot, as they are clearly discussed in the paper: for example, Hulsey et al.’s GLM- HMM used multinomial GLMs instead of Bernoulli ones, in order to include trials where no choice was made. Some less obvious differences emerge when comparing the analysis codes from the two papers. For example, Ashwood et al. followed a distinct multi-stage fitting procedure: they first fit a GLM to concatenated data from all subjects; the resulting global GLM weights were then used to initialise a global GLM-HMM; finally, the parameters obtained from this global GLM- HMM were used to initialise separate GLM-HMMs for each subject. Global GLM-HMM fitting was achieved with a tweaked version of maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation made to resemble maximum likelihood estimation (MLE); subsequent individual fits were instead achieved with “typical” MAP.

In contrast, Hulsey et al. (code available here) fit an individual multinomial GLM-HMM directly to each mouse, using their concatenated data across all sessions; further, they did so without the need for GLM parameters to initialise the GLM-HMMs. Additionally, while the analysis code shows that both MAP and MLE were used for model selection, the rest of the analysis relies only on MLE model fits. These differences contribute to a pipeline that looks very different than the one from Ashwood et al.; a short, less detailed flowchart overview of Hulsey et al.’s code (flowchart available here) highlights just how different the two analyses are, despite relying on very similar models.

Personally, making these flowcharts was very helpful for improving my understanding of how GLM-HMMs work and how they are fitted to data in practice. Beyond that though, I hope that my step-by-step overviews can also be a helpful tool for other researchers wanting to understand GLM-HMMs better or apply them to their research. All things considered, in whichever way you implement them, GLM-HMMs are a very promising tool for untangling decision-making processes. By accurately extracting latent variables from observed behaviour, this model allows, for example, to extract both neural and behavioural correlates of different decision-making strategies or engagement states (Musall et al., 2019). GLM-HMMs may also turn out to be useful aids in clinical psychology and neuropsychiatry; for example, they may help elucidate how decision-making dynamics are differently impacted by various disorders, such as depression or ADHD. With many exciting research possibilities ahead, it will be interesting to see how this model will be applied in the future.

References:

- Ashwood, Z. C., Roy, N. A., Stone, I. R., Interna@onal Brain Laboratory, Urai, A. E., Churchland, A. K., … & Pillow, J. W. (2022). Mice alternate between discrete strategies during perceptual decision-making. Nature Neuroscience, 25(2), 201-212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-01007-z

- Histed, M. H., & O’Rawe, J. F. (2022). From choices to internal states. Nature Neuroscience, 25(2), 138-139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-01008-y

- Hulsey, D., Zumwalt, K., Mazzucato, L., McCormick, D. A., & Jaramillo, S. (2023). Decision-making dynamics are predicted by arousal and uninstructed movements. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.02.530651

- Musall, S., Urai, A. E., Sussillo, D., & Churchland, A. K. (2019). Harnessing behavioral diversity to understand neural computations for cognition. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 58, 229-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2019.09.011

- Odoemene, O., Pisupati, S., Nguyen, H., & Churchland, A. K. (2018). Visual evidence accumulation guides decision-making in unrestrained mice. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(47), 10143-10155. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3478- 17.2018

- The International Brain Laboratory, Aguillon-Rodriguez, V., Angelaki, D., Bayer, H., Bonacchi, N., Carandini, M., … & Zador, A. M. (2021). Standardized and reproducible measurement of decision-making in mice. Elife, 10, e63711. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.63711

- Urai, A. E., Braun, A., & Donner, T. H. (2017). Pupil-linked arousal is driven by decision uncertainty and alters serial choice bias. Nature Communications, 8(1), 14637. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14637

- Wichmann, F. A., & Hill, N. J. (2001). The psychometric function: I. Fitting, sampling, and goodness of fit. Perception & Psychophysics, 63(8), 1293-1313. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194544

Great post, Camilla! Thanks for providing this very clear and elegant summary of our work. The flowchart is also great, and I hope it will be useful to others. (We should consider providing something similar in our future work!) Good luck with your future studies and I hope to cross paths in the future!